INTERVIEWING FOR STORY: Gathering information by talking with others

Tips and Strategies about how to talk with others to get the details you need to tell a great story--and a home-run storytelling strategy you can use today!

LISTEN, REACT, FOLLOW UP

Good reporting—gathering information—is about 80 percent interviewing. Good interviewers get as much out of a source as they possibly can in the time they are given. Most interviews are really conversations rather than stilted question-answer sessions. That means the interviewer must LISTEN to the source, REACT to the response and FOLLOW UP with appropriate questions.

Ken Metzler, in his groundbreaking book Creative Interviewing, identified the 10 biggest interviewing problems faced by reporters. (Ken Metzler was one of my journalism professors, and taught the first interviewing class at the UO school of journalism while he was writing the book.) The following material is from the streamlined stylebook I wrote for my high school students to use when I started teaching journalism.

Steps of the interviewing process

Interviews, we’ve learned from experience (and some research), generally progress through 10 stages:

1. Define the purpose of the interview.

2. Complete background research.

3. Request an appointment.

4. Preliminary planning of questions and strategy.

5. Meeting respondent/conversational icebreakers.

6. Getting down to business.

7. Establish rapport.

8. Ask the bomb.

9. Recovering.

Conclude the interview.

“What question did I not ask that you would like to answer?”

The first four stages of the interview deal with preparation. The amount of research necessary depends upon the story, your knowledge of the subject, and the time available. Once the background research is done, you plan the questioning strategy as well as some specific questions.

For family history researchers attending a family event, this means studying the family tree, following up with questions on stories you’ve heard, asking questions about favorite moments or events that shaped the person or family, and getting concrete details.

The last six stages deal with poise — or how you handle the interview. From the moment you meet the respondent, the way you handle yourself and the way you treat the respondent will dictate how the conversation will go. Your goal is to develop a give-and-take conversational style that is comfortable for both of you.

Developing rapport means establishing a relationship of trust and honesty between the interviewer and the respondent. You should try to understand what the respondent is saying by paraphrasing (putting in your own words) the thought and repeating it back to the respondent.

Once rapport is established, You can ask a sensitive question. Some interviews do not have a sensitive question, and at other times you discover it accidentally. Poise means putting the subject at ease, following up on leads, and keeping cool.

Finally, researchers have concluded that most people enjoy being interviewed and most of them would be willing to do it again, even when sensitive questions were involved.

Establishing rapport

Most successful interviewers do not use the hardline style of questioning. The truth is that communication is only possible when people feel free to express their feelings and beliefs regardless of whether the other person agrees. How can you do this?

Listen in a non-judgmental way. Paraphrase the respondent’s comments to make sure you understand what is being said.

Be involved in the interview. Don’t neglect social amenities, and remember to follow up promising leads.

Be aware of the possibility of personal change as a result of what you learn.

Tips from experienced interviewers

If possible, interview people in their own environment. The respondent will usually feel at home in a familiar place and respond more openly to your questions. Your respondent will not be distracted by a new setting. The publications office may be a familiar place to the interviewer, but to those who are unfamiliar with it, it is noisy and distracting. Another benefit to the interviewer is the chance to soak up descriptive detail and interactions between the respondent and the people with whom he or she works.

Be careful to phrase your questions in such a manner that you avoid gettting a “yes” or a “no” answer. “Brandy, you were the Prom Committee Chair this year, and from all accounts, it was the best Prom in years. The band, the decorations and the food were incredible. Can you tell us the secret to your success?” “No.” Enough said.

Be sure you are listening. Don’t be so intent on the next question that you don’t listen to what the respondent is saying. Don’t worry about the next question until you run out of follow-up questions for the answers your respondent has given you.

Your notes should reflect the words and phrases of the respondent, not your own. Yes, that means you must write down what you hear.

Interviewing is like mining for diamonds. You are not sure where the digging will lead you, but you’ll know a diamond when you see one. At this point, you have a diamond in the rough, and with a little cutting and polishing, you’ll have a gem of a story on your hands.

Most interview questions are based on what is already known, yet the purpose of an interview is to uncover new information. With that in mind, a good reporter pounces on new information, or that which clarifies or explains previously reported information. Even though you go into an interview with a definite purpose, be prepared for the unexpected — and be prepared to pursue it.

When you have completed the interview, take a moment to review your notes and make sure you have all the answers you came for. A great way to conclude an interview is to ask the respondent if it would be okay to call them if you have any questions. It eases the respondent’s fears that you will rush into print with inaccurate information. Back at the newsroom, of course, be sure to contact your source should you have any questions about what they meant or said. This gives you and your newspaper credibility the next time you need to talk with that source again. Building bridges of communication between the newspaper and the community is what it is all about. When a big story comes along, you will have sources who trust you who are willing to help you out.

Types of questions

Getting useable information from a respondent depends greatly upon asking the right type of questions. In his book Creative Interviewing, Ken Metzler identifies and describes the types of questions and strategies interviewers might use. They are briefly dealt with here.

OPENING QUESTIONS

Icebreakers — A comment or inquiry about a personal effect; talk of current events or weather; talk of mutual interests or acquaintances; use of the respondent’s name; use of good-natured kidding or banter.

First Moves — A continuation of icebreakers because they lead to questions you want to ask; report to respondent what people are saying about him or her; defuse hostility; look for humor or irony, if appropriate.

FILTER QUESTIONS—Filter questions establish a respondent’s qualifications to answer questions. It it useful whenever you are interviewing a person with unknown credentials. They enhance conversation with highly qualified sources and weaken it with poorly qualified sources.

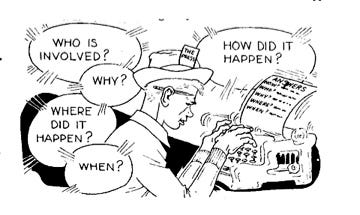

ROUTINE FACTUAL QUESTIONS—Who, What, When, Where, Why and How

NUMERICALLY DEFINING QUESTIONS—

Statistics, concrete and dynamic—How many? Can you make a comparison (He walked 120,000 miles, a distance equal to almost five times around the world at the equator.).

CONCEPTUALLY DEFINING QUESTIONS—The question is simple: Why? The hard part is trying to understand the answer.

PROBES—The probe encourages the source to explain or elaborate. You can be passive (“Hmmmm…I see….”), responsive (“Really! how interesting!), mirroring (“Thirty-three arrests…”), silence, developing (“Tell me more about….”), clarifying (“Does your boss know about them?”), diverging, and changing (“I’d like to move along to another topic….”).

SOLICITING OF QUOTATIONS

Quotes are typically shorter than having the reporter explain it. Use quotes like a dash of spice — for something special

What types of quotations should you look for? They should reveal humor of character, humor or homely aphorisms, irony, jargon, authentication, figures of speech used by respondent, authority, argumentation, sharp probes or silence.

SOLICITING OF ANECDOTES—An anecdote is a “storiette.” It concentrates on an incident or two. How do you get them? You swap stories with the respondent — one of yours for one of hers. You also play hunches and follow leads.

CREATIVE QUESTIONS—Form a hypothesis, a possible explanation, and drop it into the conversation.

###

BONUS STRATEGY: The Wall Street Journal Feature Formula. It’s this easy to get started!

-30-

Thanks to you we now have more than 264 subscribers and followers. When you Subscribe you get the latest posts in your email so you never miss a post. Posts and Notes are always free when you Subscribe.

Sharing news about a death in the family

Thank goodness there was a great deal of talking and laughing about family life experiences at Thanksgiving. As we were discussing extended family members who had died this year, there was considerable debate about the timeliness of a distant family’s intentions of memorializing their parents’ live…

How to begin your family history story, and preserve those fragile photos

Let’s begin with the assignment:

-30-