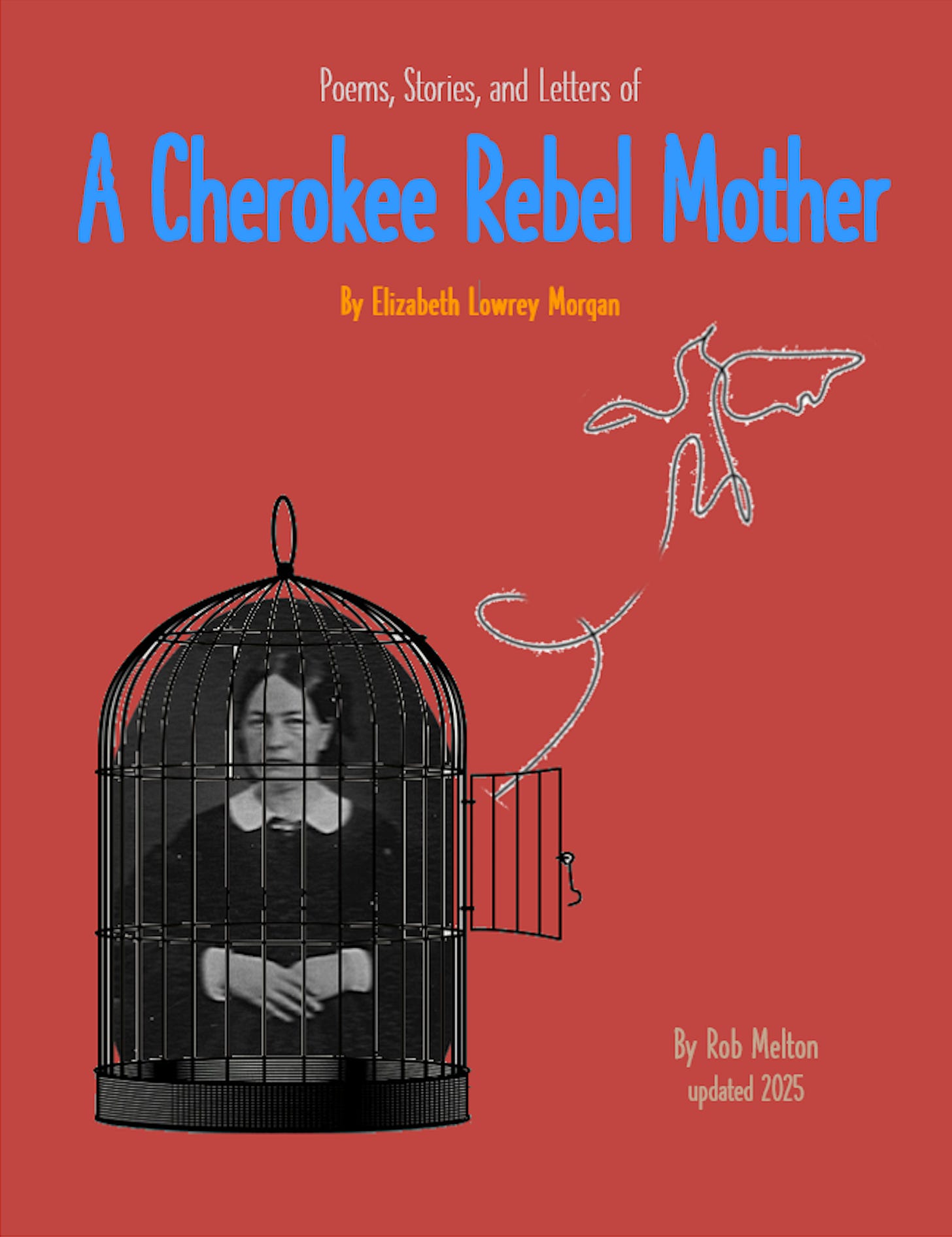

Poems, Stories, and Letters of A Cherokee Rebel Mother

Family history comes to life with the discovery of poems from a great-great-grandmother who is a descendent of Eastern Cherokees. Here's how, using her own words, we brought her story back to life.

Two years ago, out of the blue, I received an email with photocopies of long-lost poems by our great-great-grandmother Elizabeth Lowrey Morgan. For over a decade I actively asked anyone and everyone if they had ever seen a copy of the poems. My second cousin, a college professor, discovered them in a trunk in her attic in early 2023.

Other family members began helping to transcribe these handwritten poems of Elizabeth Lowrey Morgan handed down through the generations. Lucy, William Childs, Cam Teasdale, and I have worked together on a number of family history projects, but this is the biggest one to date.

Lucy worked with another cousin, Ellen Vaughan, to create the Giclee process scans of Elizabeth and her family and sent me the digital copies used in this book. (In summer of 2023, Ellen sold the portraits to the Tennessee State Museum so others could view the originals.)

I also received plenty of advice from the women in the family about what the poems mean from a woman’s perspective, although ELM’s strong voice and opinions clearly stand on their own, but any errors are my own.

I spent more than a year researching, footnoting, writing, finding family photos from our vast collection, and designing this book. This is the updated copy, after Lucy found another letter last fall that I added, after running it by professor Stuart Marshall at Sewanee, The University of the South, in Tennessee. It was a truly historic letter, solving a 150-year-old mystery.

Stuart originally found my email searching for information about our Cherokee ancestors on familysearch.org and asked if he could use it, and I said, “There are a lot more stories and photos than that if you are interested,” which he was. He included it all and then some in his first book “The Age of Junaluska: Eastern Cherokee Sovereignty in the Long Civil War Era. (2023).” We met last year at the Tennessee State Archives and I read some original letters from the Civil War battlefield by my great-grandfather, then headed out for lunch. I have a copy of his book on my shelf, and he has a copy of this book on his desk, he tells me.

It seems a particularly good time to share this story, too.

It’s free to read online. You can also order a print copy.

Here’s how I decided to introduce the cast of characters in the introduction, centering it on the women in the family:

This is the story of our great-great grandmother Elizabeth Lowrey Morgan, and it’s complicated, because all she left us were breadcrumbs to follow (more on that later), and 35 poems written in iambic pentameter[1], some of them in rhymed couplets—and allusions to Greek and Latin texts of the ancients.

It’s a story of five generations that fought for their ideals about what their country should be — and, quick summary, they were all over the map on the great debates and wars of that time. Elizabeth was born in Tennessee, the daughter and granddaughter of famous Morgan military men and successful businessmen with many children.

She was also the granddaughter of a Cherokee woman who married Joseph Sevier (originally Xavier, and descended from one of the first saints of the Catholic Church), which makes her descendants the children of Cherokees as well as a descendent of the first governor of Tennessee John Sevier — a notorious fighter who destroyed indigenous peoples’ culture and drove them from their land for immigrants.

Elizabeth herself remained very much connected to the Eastern Cherokee nation and culture. The Eastern Cherokees realized early on their survival depended upon being highly educated and wealthy. She was also a member of the Presbyterian Church in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Although Tennessee was not part of the original Confederated States of America, many Cherokees fought on the side of the South because of President Andrew Jackson and his promises to and eventual betrayals of native people.

Elizabeth’s younger sister Cherokee America moved to Oklahoma where she built her family farm empire, a right she had as a free Cherokee woman. Elizabeth and Cherokee America were close throughout their lives.

Elizabeth and her sisters were educated in New England and Knoxville schools for girls, studying the Bible and the classics, as her list of books taken from her house by the Union Army shows. It’s clear she studied classic Greek and Roman literature and poetry as well as Shakespeare, among others.

She was a poet and writer, according to an old newspaper clipping that said she was considered the “poet laureate of the Cherokee Nation,” and she hand-copied her poems into journals for each of her grandchildren. For years I asked every family member I could if they had inherited a journal of her poems.

Then one day Lucy Schumer, my second cousin, found a photocopy of the poems in an old trunk, and sent me the scans.

Almost all of the poems noted the place and year each poem was written. Several hand-written notes indicated the poems were recited by heart by her grandchildren. That was her wish — for the Cherokee people to speak her verses — and her reason for not wanting to publish or copyright her work. (It is also my reason for making it free.)

I spent a great deal of time deciphering the handwriting and researching many of the words that we no longer use. After I finished typing the first draft, I realized I needed to completely rearrange the poems section chronologically. I believe it now captures her growth as a woman, and offers clues in the footnotes to explain old and now-obscure words, phrases, and context for understanding the age she lived in.

Elizabeth wrote in almost every decade of her life (we presume there are still lost poems, as she was prolific in prose and poetry), and they chronicle every aspect of her life. Where I and several of my cousins struggled to read handwriting and were at a loss in identifying a word, we have simply put an asterisk (*) to indicate the omission.

Elizabeth wears her heart on her sleeve, as she experiences life’s joys and tragedies, love and loss, victories and defeats, daily life, as well as the natural world around her.

Most of her poems are written in iambic form (an unstressed followed by a stressed syllable[2]), Shakespeare’s chosen rhythm; unlike Shakespeare who wrote 80 percent of his lines in iambic pentameter (10 syllables), she writes in an 8/6 alternating format (found commonly in the music of her day), sometimes in rhymed couplets, sometimes in alternating rhymed lines, sometimes not rhymed at all. It is clear she was highly sought after when it came to writing poems for weddings and funerals, and again we believe there is more of her work out there.

She also wrote prose and entertained family and friends with her stories. It was said in a newspaper article that she could adeptly change her stories depending upon who was in the room. She made draft copies of the letters she sent to others, of which we have only one. If you are in possession of such a poem, story, letter, or other artifact (especially if you have an original copy) please share it with us.

One more thing: If you are a bit rusty on reading and analyzing poetry and narrative, as a former journalist, retired high school English and CTE Publishing & Broadcasting teacher, and Shakespeare enthusiast, I highly recommend these two helpful aids from my teaching days to quickly help you understand poetry and narrative, as well as the provided footnotes, sidebars, photos, illustrations, bibliography, and a bit of family history.

It is unusual to find such a complete written record of the life of a woman of the 1800s. Through the work of University of North Carolina Gainsboro and its work creating historiographies of the Native South, Dr. Stuart Marshall has woven together an even more rare story — that of the treatment of the indigenous people of the south — in his dissertation “The Age of Junaluska: Eastern Cherokee Sovereignty in the Long Civil War Era. (2023).” Elizabeth Lowrey Morgan McElrath and her son John Edgar McElrath and others are featured in his work.

Some people might say Elizabeth lived a charmed life, but that would be only half of the story. She was proud of her Cherokee heritage (she was one-eighth Cherokee according to the Dawes Enrollment, which is correct because Cherokee genealogy is matrilineal), her family (the Morgans who fought bravely in the Revolutionary War), and her social connections (Mrs. Rockefeller, among others).

A bit more about her immediate family: Elizabeth’s first husband Hugh McDowell McElrath was a successful New York City businessman, a wholesale clothing merchant with the firm of Rankin Pullman & Co, who traveled extensively. He was also involved in several mercantile ventures and land transactions in Eastern Tennessee, providing legal services as a member of the bar, as well as managing the farm in Tennessee and conducting business in North Carolina not that far from where he was born. Hugh acted briefly as a courier running Brigham Young’s encrypted July 21, 1858, message to Thomas L. Kane, along with a stash of cash, to Pennsylvania.[3]

Elizabeth and Hugh “lived for some time in South Carolina to 1860 in N.Y.,” but had never broken up their home in Tennessee, and were wealthy ($285,000 of wealth held before the Civil War, which would be worth $109,524,069.18 today[4]), until they converted all their wealth into Confederate dollars, and only had +$5,000 in U.S. dollars to their name in U. S. currency by the time the war was over ($1,921,474.90 today).

Despite their successes, Elizabeth and Hugh lived through 13 Recessions, two Panics (which brought the economy to a screeching halt, one of which was followed by a depression), and two Depressions from 1810-1882. In the 19th century, recessions frequently coincided with financial crises, something that is less common in post-WWII, believe it or not.

Despite the fact that Tennessee was not one of the original Confederate states because its people were evenly divided, according to historians, Elizabeth’s Morgan and McElrath families aligned with the Confederate States of America. I mention this because she writes about it. Elizabeth worked on the front lines of the war as a nurse, according to one letter, and the Union Army suspected she may have been a spy, as well, although they could never prove it.

We could write about the men and all of their battles and failures and successes, but this is about the women, so very briefly:

Hugh became the Tennessee Confederate Army Quartermaster (the money guy), and their son John Edgar was a Quartermaster for his unit before he became a captain. Both Hugh and John Edgar resigned from the Confederate Army in 1862, according to documents in the Tennessee State Library and Archives in Nashville, Tennessee. Hugh announced his intention to run for public office in an ad published in the spring of 1863.

John Edgar practiced law in Cleveland, Tennessee near Chattanooga, and perhaps took care of his ailing father’s affairs. John Edgar joins the bar in Knoxville, Tennessee, and practices law in Cleveland near Chattanooga. While the rest of his family moves to Oklahoma, he moves to San Francisco, California. There he practices law, is active in civic life, and successful in business ventures. He and his wife Elsie Alden have 11 children, whom Elizabeth visits often. Their connection may have been through their parents’ time in New York City, where Elsie was born. He wins a famous 1879 (U. S. Supreme Court) Circuit Court of California case Ho Ah Kow.

Hugh died on October 1, 1863, of unknown causes.

Elizabeth then married William Eblen in Oklahoma Cherokee Territory, and helped her second husband, whose wife had died, rear his children.

Oh, and one other important thing: In a podcast episode that’s worth a listen on WHAT’SHERNAME by academic sisters Dr. Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle, they describe the unique freedom Cherokee women had:

“At this time Cherokee women have way more freedom, way more education and a lot more rights than white women in the U.S. would have had. They own property, they inherit property. They are fully in charge of their own lives and their own decisions, and there’s no expectation of submission to men. … Cherokee America lived in the upper echelons of society. There was a whole group of these women, who dressed as white women, which at the time of course was Victorian garb. You know, they were smart. They were literate. They had been educated. And they were used to power.”[5]

Four generations of this extended family were right smack in the middle of everything, and they survived, adapted, moved on, started over, whether from the North or the South; educated or salt of the earth; wealthy, weathering the storms and taking sides; networked with the movers and shakers of the day, until they finally decided to walk away from it all to start over again. Sound familiar? You bet! In short:

Elizabeth leaves Tennessee for Tahlequah, Oklahoma, to embrace her Cherokee culture, and to be with her chosen people and family. She devotes herself to the Cherokee Girls Seminary and other Cherokee causes, continuing to writing and travel.

Ellen marries James Cross Morris in Tennessee and they, too, leave for Oklahoma Territory with their six children.

Susan dies in Tennessee, leaving her husband with three children. He leaves Tennessee with the rest of the family for Oklahoma Territory.

Clifford dies when he is three years old.

John Edgar joins the bar in Knoxville, Tennessee, and practices law in Cleveland near Chattanooga. While the rest of his family moves to Oklahoma, he moves to San Francisco, California. There he practices law, is active in civic life, and successful in business ventures. He and his wife Elsie Alden have 11 children, whom Elizabeth visits often. He wins a famous 1879 (U. S. Supreme Court) Circuit Court of California case Ho Ah Kow. [6]

What follows are the exact words (as best we were able to transcribe them, anyway) of a talented 19th century Cherokee woman who wrote and told poems and stories throughout her life that capture the joy and grief and realities of her life and times. Much has been published about Elizabeth’s sister Cherokee America Morgan Rogers, who was the heart of the newspapers that loved to cover her Morgan family, but it is fair to say that Elizabeth Lowrey Morgan was the soul.

—Rob Melton, great-great-grandson

robmelt@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

All along our family history journey, we have had help and moral support. Thanks to…

Lucy Schumer and Toby Childs, co-collaborators on many projects, of which this is just one.

Marion McElrath, for passing along our family history as written by her father John Edgar McElrath.

Alden McElrath, my grandfather, who shared his love of family, food, and fun with all of us.

Innes McElrath Melton, my mother, for writing down the stories and sharing the family history and names she knew in the photographs.

Ellen Vaughan, for creating the giclée process images of the McElrath portraits at Lucy Schumer’s suggestion. Ellen met Lucy when the paintings were photographed. In 2023 Ellen Vaughn sold the Samuel Shaver paintings to the Tennessee State Museum.

Cousin Cameron Corlett-Teasdale, for helping me to decipher handwriting during a smoky central Oregon summer week.

Kate Melton, mother of our children, who helped and offered advice and counsel with every aspect of this project from conception to completion. We did this for our children and grandchildren, of course!

My siblings and cousins for asking good questions, and helping me find a way to tell this story and others. Feel free to tell your own stories.

Dr. Stuart Marshall, historian of the Native South, for sharing his doctoral dissertation, a historiography using stories from our family and others that helped me appreciate in a whole new way the background story of the family, and a wonderful lunch with our partners when we met in Nashville.

Laura Spann, who made digital records of the Knoxville Presbyterian Church records that included the McElrath and Morgan families and shared them with me.

Renee Willingham Hamilton, a family history researcher and veteran, who researches and submits veterans for recognition through DAR, SAR, and other organizations.

Elizabeth Eblen for sending photos of Elizabeth Lowrey Morgan’s Cherokee beads, and for helping track down other stories and artifacts.

The Tennessee State Museum, Richard White, Chief Curator and Candice Roland Candeto, Senior Curator of Fine Art, for a tour and conversation in preparation for an exhibit of the paintings.

The Tennessee State Library and Archives

The Library Of Congress for its free historical resources

The Multnomah County Library for providing free family history research during the pandemic

[1] For an excellent tool to help you analyze her poetry and others, see “Elements of Poetry” by Paul Reuben in the bibliography

[2] Fun tip, from book Shakespeare Aloud by Edward S. Brubaker (early Festival Director of Oregon Shakespeare Festival): The words with an accented syllable in a line of iambic pentameter carry the meaning of the line. There were no mics in Shakespeare’s time. If the audience heard only the accented syllables, they could understand what was going on.

[3] Hugh McElrath’s role in all this was to do Brigham Young the favor of couriering an encrypted message intended for Thomas L. Kane, a non-Mormon confidant of Young, back to the East during Mr. McElrath’s planned return to New York. Utah Historical Quarterly, Volume 89, Number 4, 2021.

[4] “Purchasing Power Today of a US Dollar Transaction in the Past,” Measuring Worth, 2023. measuringworth.com is a useful tool for family history researchers. URL: www.measuringworth.com/ppowerus

[5] Dr. Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle. “The Farmer Cherokee America Rogers.” WHA’TSHERNAME podcast. July 29, 2019. whatshernamepodcast.com/cherokee-america-rogers. Accessed 4 Sept 2023.

[6] APIA Biography ProjectBlurb Books

It’s free to read online. You can also order a print copy or a PDF of the book.

-30-

Amazing! The amount of work in putting it together is obvious—and so rewarding. I am sure it will become part of curriculum of some kind over time. Don’t hesitate to offer it to colleges as part of their libraries. This is the kind of history and trading Americans need more of.

Wow! This is fascinating. Thank you for sharing your process and results.