Four questions guide lessons, and five strategies to engage student learning

As a young high school teacher, I deployed the best learning strategies. You can, too. Here's how, in a nutshell.

The student who needs to know why they need to know must be first. Students who need to know what to learn are next. Students who need to know how to do it are next. Students who can demonstrate mastery in a final project of their choosing. No one gets left out. Everyone wins.

This is a process piece that explains effective lesson design, which helps teachers implement a continuous improvement process in the classroom involving student self-reflection and putting them in charge of their learning, and the unspoken barriers that get in the way.

If you want to dig right in to my research, planning documents, and implementation, start here.

The journey began with a Dr. Bernice McCarthy “Designing with 4MAT Course” that our school district sponsored. A trainer guided us through the 4MAT process. It was groundbreaking. This is still the model for 4MAT training today:

The approach is rock-solid and logical. As a young teacher with a journalism background, a headline is supposed to give readers a reason to read the story; a benefit headline for an ad does the same thing. This approach made a lot of sense to me. Why shouldn’t the student’s first question be “Why do I need (to learn) this?”

The second question should be “What do I need to know?” in which they further explore content and learn specific concepts.

The third question “How do I do it?” starts with a review of the new concepts to reinforce what they have learned, and to use that information to practice the skills they will need for the final project.

The last question is “How do I integrate this into what I already know?” and is the step that is often missing but is necessary for the student to personalize the knowledge through a project that will be shared with the table group, class, and teacher.

As I worked with this structure as a young teacher, I realized I needed a way to organize the lesson from my point of view, too, and I used my own understanding of lesson design and 4MAT to create a teacher worksheet wheel to use when I needed to plan a new lesson plan.

Before I completed my master’s degree in Education at Portland State University, I partnered with an elementary teacher to explore the effectiveness of 4MAT Lesson Design. He found the lesson creation process highly successful with his students, as the narrative discusses. Our hypothesis was confirmed. I wrote and designed this paper for a PSU class, and it became one of the “handouts” for college classes I taught for high school journalism teachers. (I was trained at UO in print and broadcast journalism, including graphic design and typography.) Why? I wanted to share it with others.

One professor in another class was genuinely troubled by the design, finding it hard to believe a student could have done it. Compliment accepted. I had bigger plans; it became one of the “handouts” for teacher sessions at national journalism conventions and college classes I taught, including for 16 years at the University of Iowa School of Journalism for high school journalism teachers.

Students won’t know if you don’t teach them #1: A way to engage them in selecting and presenting a portfolio of their best work for the semester/term.

I realize I’m starting with the end of the semester, but the last thing I learned is perhaps the most important. The truth is, when you are working with at-risk students of any type, they have given up trying before they ever arrived in your class. I’m a bit curious, extroverted, and unafraid of the truth. I asked questions. In their experience, the more work they submitted, the worse their grade became because they were learning something new. I asked them, “What if your grade was based on you trying your best, with multiple revisions and feedback from your table group and me? What if at the end of the semester your grade was based on your best work? A portfolio of what you learned about reading and writing?”

One of their questions was, “Where are we going to keep all of our work? I don’t have a binder or a place at home.” That’s when I begged and borrowed for additional file cabinets, and each student had their own folder they put all of their work in at the end of class — and they weren’t allowed to remove it without me saying something like, “Swear an oath that you are absolutely going to return this to me before school tomorrow or you are going to fail this class! Promise? Really? Okay, then, just this one time!”

Well that did it. As with the “Write Before Writing” assignment (below), where they had to write comments on the page and answer all the open-book questions as well as learn the skill and demonstrate it, this was the final project at the end of every semester: The Writing Portfolio. What you’ll notice is that it approaches things from multiple learning styles — cartoons, the quizzes, writings, discussions.

After the first semester I chose several portfolios that demonstrated growth to show to the class, without the title page where the name would be, just to show it didn’t need to be perfect to be good. Students usually were willing to share their portfolio in my presentation to their class, and it was always fun and gave them new things to think about.

At the end of every semester students were required to create a portfolio of their best work of the semester, write a process paper about how they wrote the best paper, and also had to create a cartoon illustrating the writing process (to make sure they were using all parts of their brain). Of course there was always a rubric for everything we did, including the Portfolio Rubric. Always great results -- and freed them to explore writing knowing their final grade in the class would be based only on their best work and their reflection essay and cartoon (all assignments were required to be turned in, preferably on time).

Students won’t know if you don’t teach them #2: A way to engage students using their own preferred learning style.

As I mentioned at the start, from my experiences I knew the skills I needed were learned through experience and from mentors, an early Aha! moment for me. I needed it my way. Others also showed me that in various ways.

I attended Santa Rosa Junior College, excellent preparation for U.C. Berkeley or Stanford, but my dad was a teacher and I was an honors student who transferred to the University of Oregon to study and graduate in journalism with minors in English and political science. A hands-on Shakespeare class required a final hands-on project of our choice to personalize our knowledge. Some students made elaborate costumes for a Shakespeare character, others build miniature sets, lighting schematics, even performances. I traveled up to Ashland, Oregon, to interview Angus L. Bowmer and take photographs to produce a video about the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

When I was 14, my brother and I stood in the groundling area behind the low shrubs at the back of the theater and were instant fans. When OSF started Portland Center Stage, I became a docent, fed actors at dress rehearsals, and led tours for 29 years until they ended the volunteer program.

Most importantly, I taught Shakespeare (and other plays) as Drama with a capital D.

At UO, one of my last classes was taught by Mary Hartman, the Oregon Scholastic Press Secretary whose husband was the editor of the Eugene Register-Guard, and who taught a teaching journalism class for new teachers. (I thought it would be easy — and it was also fun.) At the conclusion of the class, she told me “You’d be a great journalism teacher!” I laughed and told her there was one thing I never wanted to be and that a teacher like my dad. A few years later I was back studying to be a journalism teacher, but only temporarily!

After my clips of stories from the weeklies in northern California I worked for, I landed a job at a rural daily newspaper in Oregon, and after getting married and earning below the federal poverty limit in wages, returned to get my teaching license — only to start at the lowest-paying district in the state that was below the poverty line!

After five great years there, winning our first Top Ten high school newspapers in the nation, I was recruited to Portland to teach journalism. They doubled my pay and I taught journalism and photography and one or two Freshman English classes.

I quickly learned that was where all the “fun” classes (drama, choir, band, electives) recruited talent. It was an audition of sorts and I had to make it challenging, fun, and interesting.

My lesson planning unit approach centers teaching on genre while focusing on the processes students use to learn, which I based on my training in Bernice McCarthy’s 4MAT: Motivate, Inform, Coach, and Integrate. This focuses students on developing the skills they need and gives them a variety of ways to practice it. I adapted McCarthy’s approach for my journalism and English classes.

I wrote Elements of Teaching To All Learners during my master’s degree work. (My thesis was a statistical study that proved the predictability of students receiving passing scores on the state writing assessment based on the number of prewriting skills they used based, which was based on a semester portfolio map of their prewriting skills.)

While some of the works cited on Page 9 have been dismissed on scholarly grounds, i.e., Brain Gym, all of the listed sources in the Works Cited helped me think about the needs of learners from many different perspectives.

In the early 1980s PPS offered the first Bernice McCarthy Designing With 4MAT workshop and it inspired me to explore, using classroom research, what worked well for curriculum planning and execution. A graduate school classmate volunteered to implement a lesson plan using this approach and found it worked well for elementary school students. That was also verified in my own work with high school students.

The planning document on page 13 discusses the goal for the teacher — Motivate, Inform, Coach, Integrate — while posing the questions students ask, in the order they need the information — Why do I need to learn this? What do I need to learn? How do I use this information? If I’m going to do a project to demonstrate what I have learned, what would it be?

Students won’t know if you don’t teach them #3: A way to engage students at the end of a lesson to help you improve the lesson for next time.

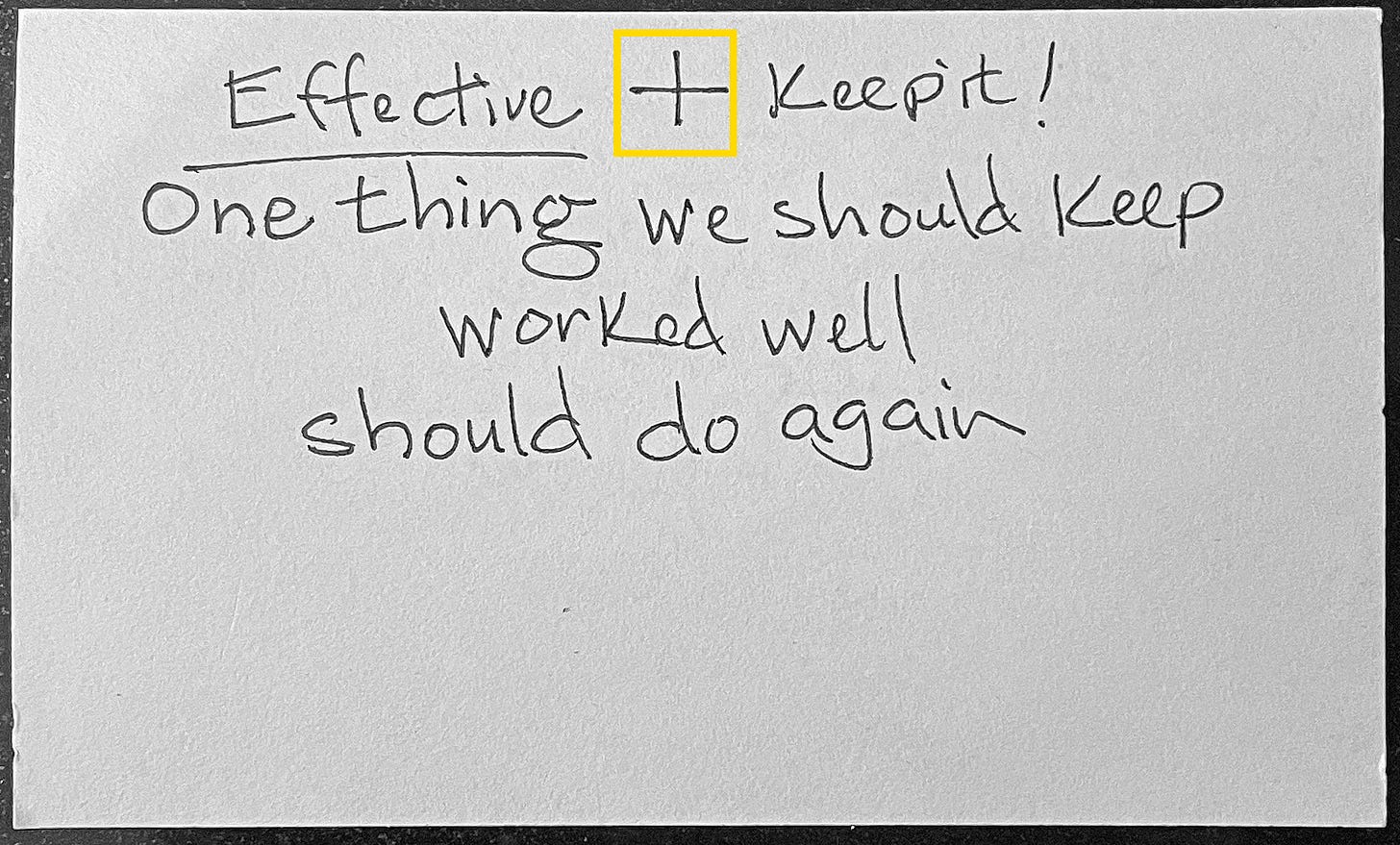

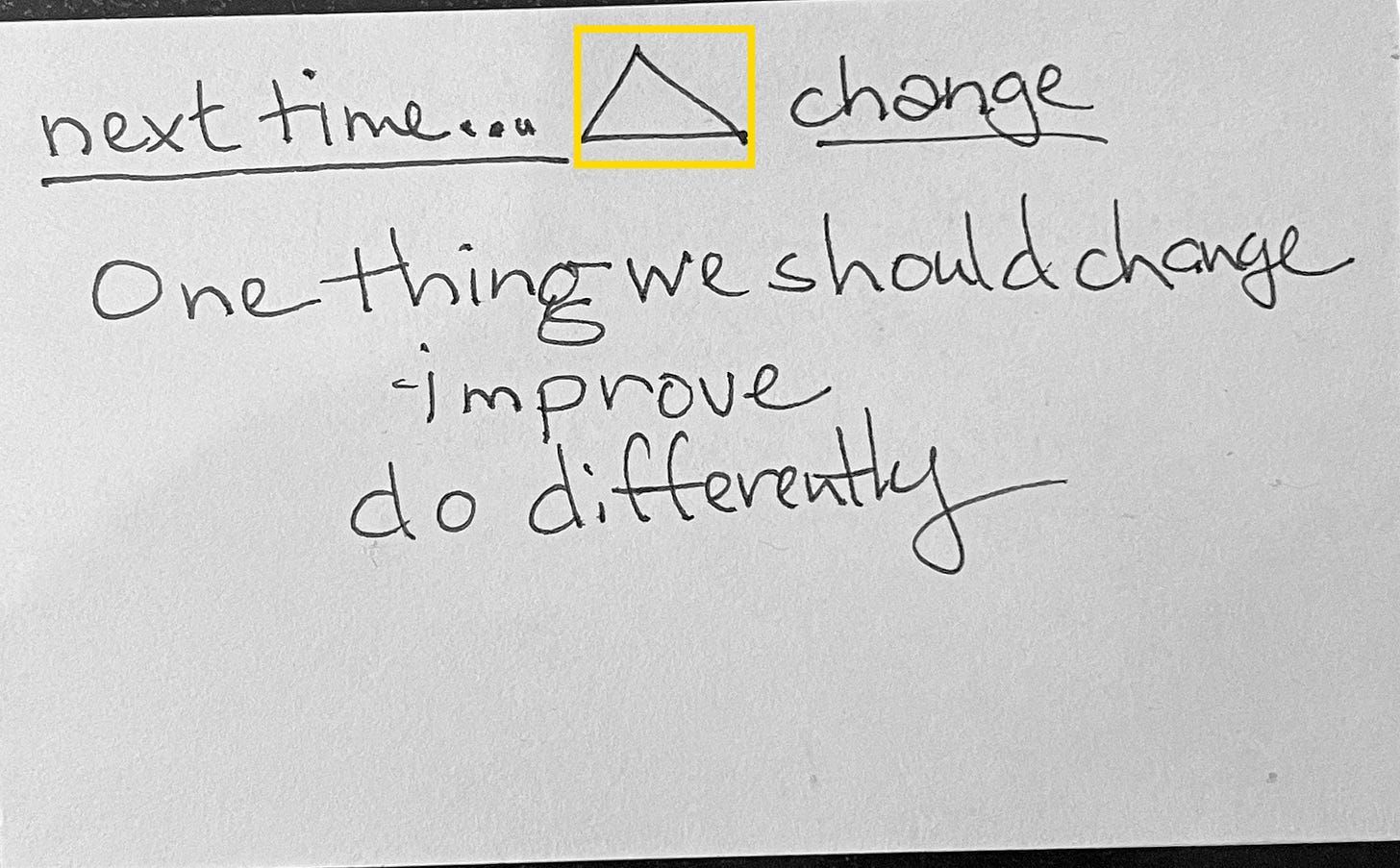

PLUS/DELTA

The other major change I made was to have students complete a Plus/Delta evaluation on a 3x5 card of every unit I taught. It’s a continuous improvement model that was shared at a school meeting by Portland General Electric (before it was briefly owned by Enron).

This is the best activity I have ever used with a group of people — whether they are students, co-workers, or volunteers — to assess the end of a project, lesson, activity, or unit (you get the idea).

Believe it or not, I had students come up to me after the lesson was complete and ask me, “How did you come up with such an amazing lesson?” to which I always replied, “I read your Plus/Delta cards after every lesson and made changes based on what you told me.”

Imagine if we listened to all of our students and modified our lessons based on one thing to keep and one thing to change.

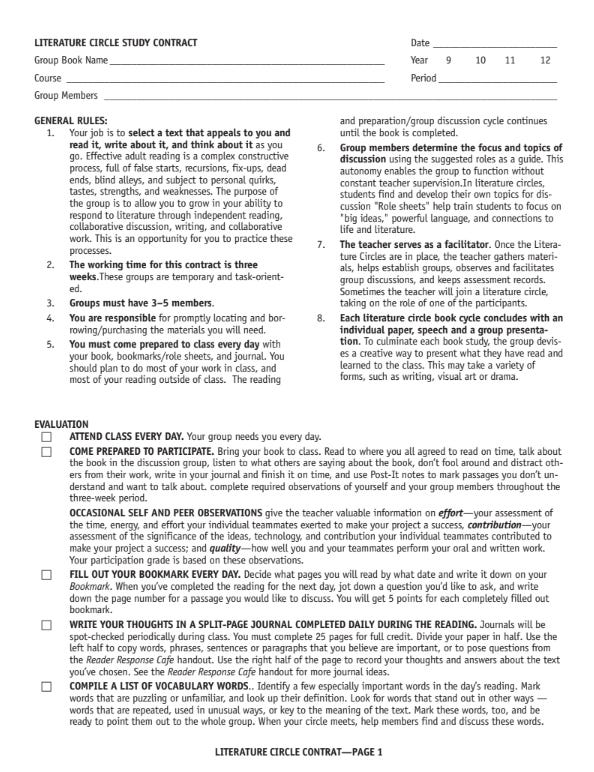

Students won’t know if you don’t teach them #4: A way to engage students in small groups that leaves nothing to chance — spell it out for them.

I started each of the genre-focused lessons in the present, always starting with a how-it-works genre handout and an open-book quiz that came with it, then usually broke students into table groups depending on the unit and needs. I could quickly answer specific questions and get them back on track. All of these lessons followed the lesson design discussed here.

For example, when studying contemporary novels, students first studied the Elements of Narrative, then they chose one of 8 multicultural contemporary novels to read, and their group presented it to the class using the above Literature Circle handout. We did similar things with poems, plays, and such. Then we explored how earlier literary works influenced what we do today — because at that point, students were prepared and experienced with all the tools they would need to be successful at it.

With this knowledge, you will understand I did this with the help of willing administrators who were willing to invest in small sets of 15 contemporary American multicultural novels for three periods of Literature Circles.

Students won’t know if you don’t teach them #5: A way to engage students learning how think about the prewriting and writing process with an open-book quiz.

Every English student I ever taught started the year by reading this (which I discovered in the bowels of the University of Oregon Library in the stacks and reformatted), annotating it in the margins -- 5 responses per page -- and then answering the questions at the end. Note that the recall questions are in order presented (the key on the wall showed them where the answer was and no, they only used it if they couldn’t find it first) and the rest are thinking questions personalized by each student (no wrong answers). I later used this technique to prepare students to pass the state’s writing requirement for graduation. This led to the end-of-the-semester portfolio project.

Almost needless to say, except no one I know ever does this, they attempted to learn something from ALL assignments, and worked in groups to discuss and help each other out. It all started with this piece.

The article, “Write Before Writing” by Donald M. Murray, originally appeared in College Composition and Communication (December 1978): 375–381. I reformatted it for the copy machine and my students, and added the instructions and margins so they could write notes.

-30-

Read this! https://open.substack.com/pub/terryu/p/reclaiming-the-lost-art-of-teaching

Wow, just wow