Prewriting secrets that turn students into Real Writers who can explain their process

And why they do significantly better on mandated writing tests

Note: When I discovered this seminal article while doing post-graduate work, it was one of those aha! moments when time stands still. Donald M. Murray was a writing coach for a newspaper, and his insights came from coaching journalists who gathered and wrote stories every day. All writers learn these things, but Murray made them explicit for the first time. Yet it is rare even today to find any academic discussion of prewriting as an essential tool to understand the writing process that leads to a first draft. I set about to change that. Over the years, more writers are starting to share their own writing process.

This reading is required reading for all my students at the beginning of the year. Here’s a quick outline of the text for you:

I. There is one principal force which keeps writers from writing: Resistance

II. There are four positive forces which help writers move forward to a completed draft:

Increasing information

Increasing concern

A waiting audience

An approaching deadline

III. There are eight signals which say Write (you only need one to start writing):

Genres

Point of view

Voice

News

Line

Image

Pattern

Problem to be solved

IV. Implications for teaching writing

I formatted the article for students to write comments and underline things of interest on each page. I’ve used this with high school, college, and graduate school students with great results.

Then I created a series of questions, in order of the text, to prompt a close reading and response to the text. I then posed some reflective questions to elevate their thinking.

Finally, I asked them a series of questions to think about how they write. Often, the first time they encounter these questions, the answer was “I’d never thought of that before.” We periodically updated their answers—by drawing a quick writing process diagram.

We’ll talk about portfolios in another post, but they kept all their work in a folder in the classroom and eventually had to rank-order their best work and write a reflective paper on their writing process and the lessons they had learned, both good and bad.

Their final portfolios at the end of each semester, as well as a state-mandated writing test and results, became the raw material for my master’s thesis. In my statistical analysis, I proved there is a significant relationship between the number of prewriting strategies students say they use and their success as writers on a carefully constructed measure of their writing ability.

Directions: Download the reading, highlight and add your comments and thoughts on the right, and answer all the questions. Then draw a diagram, preferably not linear, for your own writing process. It should show recursive steps and detours, using drawings and just a few words. After you complete the diagram, explain your writing process to someone else, and have some fun with it!

Digital stickers for sharing or telling us in comments what you discovered, or for trying it out with your own students!

Directions: Download and print the reading “Write Before Writing” that I use with students, and react to the text by underlining or highlighting text, and writing at least five notes per page in the white space on the right. Answer the detailed questions about the text on a separate piece of paper. The questions are in the order presented in text. The next two sets of questions help students young and old personal what they have learned.

The article below, “Write Before Writing” by Donald M. Murray, originally appeared in College Composition and Communication (December 1978): 375–381.

BY DONALD M. MURRAY

We command our students to write and grow frustrated when our “bad” students hesitate, stare out the window, dawdle over blank paper, give up and say, “I can’t write,” while the “good” students smugly pass their papers in before the end of the period.

When publishing writers visit such classrooms, however, they are astonished at students who can write on command, ejaculating correct little essays without thought, for writers have to write before writing.

The writers were the students who dawdled, stared out windows, and, more often than we like to admit, didn’t do well in English — or in school.

One reason may be that few teachers have ever allowed adequate time for prewriting, that essential stage in writing which precedes a completed first draft. And even the curricula plans and textbooks which attempt to deal with prewriting usually pass over it rather quickly, referring only to the techniques of outlining, note-taking, or journal-making, not revealing the complicated process writers work through to get to the first draft.

Writing teachers, however, should give careful attention to what happens between the moment the writer receives an idea or an assignment and the moment the first completed draft is begun. We need to understand, as well as we can, the complicated and intertwining processes of perception and conception through language.

In actual practice, of course, these stages overlap and interact with one another, but to understand what goes on we must separate them and look at them artificially, the way we break down any skill to study it.

First of all, we must get out of the stands where we observe the process of writing from a distance — and after the fact — and get on the field where we can understand the pressures under which the writer operates. On the field, we will discover there is one principal negative force which keeps the writer from writing and four positive forces which help the writer move forward to a completed draft.

RESISTANCE TO WRITING

The negative force is resistance to writing, one of the great natural forces of nature. It may be called The Law of Delay: that writing which can be delayed, will be. Teachers and writers too often consider resistance to writing evil, when, in fact, it is necessary.

When I get an idea for a poem or an article or a talk or a short story, I feel myself consciously draw away from it. I seek procrastination and delay. There must be time for the seed of the idea to be nurtured in the mind. Far better writers than I have felt the same way. Over his writing desk Franz Kafka had one word, “Wait.” William Wordsworth talked of the writer’s “wise passiveness.” Naturalist Annie Dillard recently said, “I’m waiting. I usually get my ideas in November, and I start writing in January. I’m waiting.” Denise Levertov says, “If … somewhere in the vicinity there is a poem, then, no, I don’t do anything about it, I wait.”

Even the most productive writers are expert dawdlers, doers of unnecessary errands, seekers of interruptions — trials to their wives or husbands, friends, associates, and themselves. They sharpen well-pointed pencils and go out to buy more blank paper, rearrange offices, wander through libraries and bookstores, chop wood, walk, drive, make unnecessary calls, nap, daydream, and try not “consciously” to think about what they are going to write so they can think subconsciously about it.

Writers fear this delay, for they can name colleagues who have made a career of delay, whose great unwritten books will never be written, but, somehow, those writers who write must have the faith to sustain themselves through the necessity of delay.

FORCES FOR WRITING

In addition to that faith, writers feel four pressures that move them forward towards the first draft.

The first is increasing information about the subject. Once a writer decides on a subject or accepts and assignment, information about the subject seems to attach itself to the writer. The writer’s perception apparatus finds significance in what the writer observes or overhears or reads or thinks or remembers. The writer becomes a magnet for specific details, insights, anecdotes, statistics, connecting thoughts, references. The subject itself seems to take hold of the writer’s experience, turning everything that happens to the writer into material. And this inventory of information creates pressure that moves the writer forward towards the first draft.

Usually the writer feels an increasing concern for the subject. The more a writer knows about the subject, the more the writer begins to feel about the subject. The writer cares that the subject be ordered and shared. The concern, which at first is a vague interest in the writer’s mind, often becomes an obsession until it is communicated. Winston Churchill said, “Writing a book was an adventure. To begin with, it was a toy, and amusement; then it became a mistress, and then a master. And then a tyrant.”

The writer becomes aware of a waiting audience, potential readers who want or need to know what the writer has to say. Writing is an act of arrogance and communication. The writer rarely writes just for himself or herself, but for others who may be informed, entertained, or persuaded by what the writer has to say.

And perhaps most important of all, is the approaching deadline, which moves closer day by day at a terrifying and accelerating rate. Few writers publish without deadlines, which are imposed by others or by themselves. The deadline is real, absolute, stern, and commanding.

REHEARSAL FOR WRITING

What the writer does under the pressure not to write and the four countervailing pressures to write is best described by the word rehearsal, which I first heard used by Dr. Donald Graves of the University of New Hampshire to describe what he saw young children doing as they began to write. He watched them draw what they would write and heard them, as we all have, speaking aloud what they might say on the page before they wrote. If you walk through editorial offices or a newspaper city room, you will see lips moving and hear expert professionals muttering and whispering to themselves as they write. Rehearsal is a normal part of writing, but it took a trained observer, such as Dr. Graves, to identify its significance.

Rehearsal covers much more than the muttering of struggling writers. As Dr. Graves points out, productive writers are “in a state of rehearsal all the time.” Rehearsal usually begins with an unwritten dialogue within the writer’s mind. “All of a sudden I discover what I have been thinking about a play,” says Edward Albee. “This is usually between six months and a year before I actually sit down and begin typing it out.” The writer thinks about characters or arguments, about plot or structure, about words and lines. The writer usually hears something which is similar to what Wallace Stevens must have heard as he walked through his insurance office working out poems in his head.

What the writer hears in his or her head usually evolves into note-taking. This may be simple brainstorming, the jotting down of random bits of information which may connect themselves into a pattern later on, or it may be journal-writing, a written dialogue between the writer and the subject. It may even become research recorded in a formal structure of note-taking.

Sometimes the writer not only talks to himself or herself, but to others — collaborators, editors, teachers, friends — working out the piece of writing in oral language with someone else who can enter into the process of discovery with the writer.

For most writers, the informal notes turn into lists, outlines, titles, leads, ordered fragments, all sketches of what later may be written, devices to catch a possible order that exists in the chaos of the subject.

In the final stage of rehearsal, the writer produces test drafts, written or unwritten. Sometimes they are called discovery drafts or trial runs or false starts that the writer doesn’t think will be false. All writing is experimental, and the writer must come to the point where drafts are attempted in the writer’s head and on paper.

Some writers seem to work more in their head, and others more on paper. Susan Sowers, a researcher at the University of New Hampshire, examining the writing processes of a group of graduate students found a division … between those who make most discoveries during prewriting and those who make most discoveries during writing and revision. The discoveries include the whole range from insights into personal issues to task-related organizational and content insight. The earlier the stage at which insights occur, the greater the drudgery associated with the writing-rewriting tasks. It may be that we resemble the young reflective and reactive writers. The less developmentally mature reactive writers enjoy writing more than reflective writers. They may use writing as a rehearsal for thinking just as young, reactive writers draw to rehearse writing. The younger and older reflective writers do not need to rehearse by drawing to write or by writing to think clearly or to discover new relationships and significant content.

This concept deserves more investigation. We need to know about both the reflective and reactive prewriting mode. We need to see if there are developmental changes in students, if they move from one mode to another as they mature, and we need to see if one mode is more important in certain writing tasks than others. We must, in every way possible, explore the significant writing stage of rehearsal which has rarely been described in the literature on the writing process.

THE SIGNALS WHICH SAY “WRITE”

During the rehearsal process, the experienced writer sees signals which tell the writer how to control the subject and produce a working first draft. The writer, Rebecca Rule, points out that in some cases when the subject is found, the way to deal with it is inherent in the subject. The subject itself is the signal. Most writers have experienced this quick passing through of the prewriting process. The line is given and the poem is clear; a character gets up and walks the writer through the story; the newspaperman attends a press conference, hears a quote, sees the lead and the entire structure of the article instantly. But many times the process is far less clear. The writer is assigned a subject or chooses one and then is lost.

E. B. White testifies, “I never knew in the morning how the day was going to develop. I was like a hunter, hoping to catch sight of a rabbit.” Denise Levertov says “You can smell the poem before you see it.” Most writers know these feelings, but students who have never seen a rabbit dart across their writing desks or smelled a poem need to know the signals which tell them that a piece of writing is near.

What does the writer recognize which gives a sense of closure, a way of handling a diffuse and overwhelming subject? There seem to be eight principal signals to which writers respond.

One signal is genre. Most writers view the world as a fiction writer, a reporter, a poet, or an historian. The writer sees experience as a plot or a lyric poem or a news story or a chronicle. The writer uses such literary traditions to see and understand life.

“Ideas come to a writer because he has trained his mind to seek them out,” says Brian Garfield. “Thus when he observes or reads or is exposed to a character or event, his mind sees the story possibilities in it and he begins to compose a dramatic structure in his mind. This process is incessant. Now and then it leads to something that will become a novel. But it’s mainly an attitude: a way of looking at things; a habit of examining everything one perceives as potential material for a story.”

Genre is a powerful but dangerous lens. It both clarifies and limits. The writer and the student must be careful not to see life merely in the stereotype form with which he or she is most familiar but to look at life with all of the possibilities of the genre in mind and to attempt to look at life through different genre.

Another signal the writer looks for is point of view. This can be an opinion towards the subject or a position from which the writer — and the reader — studies the subject.

A tenement fire could inspire the writer to speak out against tenements, dangerous space-heating systems, a fire-department budget cut. The fire might also be seen from the point of view of the people who were the victims or who escaped or who came home to find their home gone. It may be told from the point of view of a fireman, an arsonist, an insurance investigator, a fire-safety engineer, a real-estate planner, a housing inspector, a landlord, a spectator, as well as the victim. The list could go on.

Still another way the writer sees the subject is through voice. As the writer rehearses, in the writer’s head and on paper, the writer listens to the sound of the language as a clue to the meaning in the subject and the writer’s attitude toward that meaning. Voice is often the force which drives a piece of writing forward, which illuminates the subject for the writer and the reader.

A writer may, for example, start to write a test draft with detached unconcern and find that the language appearing on the page reveals anger or passionate concern. The writer who starts to write a solemn report of a meeting may hear a smile and then a laugh in his own words and go on to produce a humorous column.

News is an important signal for many writers who ask what the reader needs to know or would like to know. Those prolific authors of nature books, Lorus and Margery Milne, organize their books and each chapter in the books around what is new in the field. Between assignment and draft they are constantly looking for the latest news they can pass along to their readers. When they find what is new, then they know how to organize their writing.

Writers constantly wait for the line which is given. For most writers, there is an enormous difference between a thesis or an idea or a concept and an actual line, for the line itself has resonance. A single line can imply a voice, a tone, a pace, a whole way of treating a subject. Joseph Heller tells about the signal which produced his novel Something Happened:

I begin with a first sentence that is independent of any conscious preparation. Most often nothing comes out of it: a sentence will come to mind that doesn’t lead to a second sentence. Sometimes it will lead to thirty sentences which then come to a dead end. I was alone on the deck. As I sat there worrying and wondering what to do, one of those first lines suddenly came to mind: “In the office in which I work, there are four people of whom I am afraid. Each of these four people is afraid of five people.” Immediately, the lines presented a whole explosion of possibilities and choices — characters (working in a corporation), a tone, a mood of anxiety, or of insecurity. In that first hour (before someone came along and asked me to go to the beach) I knew the beginning, the ending, most of the middle, the whole scene of that particular “something” that was going to happen; I knew about the brain-damaged child, and especially, of course, about Bob Slocum, my protagonist, and what frightened him, that he wanted to be liked, that his immediate hope was to be allowed to make a three-minute speech at the company convention. Many of the actual lines throughout the book came to me — the entire “something happened” scene with those solar plexus lines (beginning with the doctor’s statement and ending with “Don’t tell my wife” and the rest of them) all coming to me in that first hour on that Fire Island deck. Eventually I found a different opening chapter with a different first line (“I get the willies when I see closed doors”) but I kept the original, which had spurred everything, to start off the second section.

Newspapermen are able to write quickly and effectively under pressure because they become skillful at identifying a lead, that first line — or two or three — which will inform and entice the reader and which, of course, also gives the writer control over the subject. As an editorial writer, I found that finding the title first gave me control over the subject. Each title became, in effect, a pre-draft, so that in listing potential titles I would come to one which would be a signal as to how the whole editorial could be written.

Poets and fiction writers often receive their signals in terms of an image. Sometimes this image is static; other times it is moving picture in the writer’s mind. When Gabriel Garcia Marquez was asked what the starting point of his novels was, he answered, “A completely visual image … the starting point of Leaf Storm is an old man taking his grandson to a funeral, in No One Writes to the Colonel, it’s an old man waiting, and in One Hundred Years, an old man taking his grandson to the fair to find out what ice is.” William Faulkner was quoted as saying, “It begins with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does.” It’s a comment which seems facetious — if you’re not a fiction writer. Joyce Carol Oates adds, “I visualize the characters completely; I have heard their dialogue, I know how they speak, what they want, who they are, nearly everything about them.”

Although image has been testified to mostly by imaginative writers, where it is obviously most appropriate, I think research would show that nonfiction writers often see an image as the signal. The person, for example, writing a memo about a manufacturing procedure may see the assembly line in his or her mind. The politician arguing for a pension law may see a person robbed of a pension, and by seeing that person know how to organize a speech or the draft of a new law.

Many writers know they are ready to write when they see a pattern in a subject. This pattern is usually quite different from what we think of as an outline, which is linear and goes from beginning to end. Usually the writer sees something which might be called a gestalt, which is, in the words of the dictionary, “a unified physical, psychological, or symbolic configuration having properties that cannot be derived from its parts.” The writer usually in a moment sees the entire piece of writing as a shape, a form, something that is more than all of its parts, something that is entire and is represented in his or her mind, and probably on paper, by a shape.

Marge Piercy says, “I think that the beginning of fiction, of the story, has to do with the perception of pattern in event.” Leonard Gardner, in talking of his fine novel Fat City, said, “I had a definite design in mind. I had a sense of circle … of closing the circle at the end.” John Updike says, “I really begin with some kind of solid, coherent image, some notion of the shape of the book and even of its texture. The Poorhouse Fair was meant to have a sort of wide shape. Rabbit, Run was kind of zigzag. The Centaur was sort of a sandwich.”

We have interviews with imaginative writers about the writing process, but rarely interviews with science writers, business writers, political writers, journalists, ghost writers, legal writers, medical writers — examples of effective writers who use language to inform and persuade. I am convinced that such research would reveal that they also see patterns or gestalts which carry them from idea to draft.

“It’s not the answer that enlightens but the question,” says Ionesco. This insight into what the writer is looking for is one of the most significant considerations in trying to understand the freewriting process. A most significant book based on more than ten years of study of art students, The Creative Vision, A Longitudinal Study of Problem-Finding in Art, by Jacob W. Getzels and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, has documented how the most creative students are those who come up with the problem to be solved rather than a quick answer. The signal to the creative person may well be the problem, which will be solved through the writing.

We need to take all the concepts of invention from classical rhetoric and combine them with what we know from modern psychology, from studies of creativity, from writers’ testimony about the prewriting process. Most of all, we need to observe successful students and writers during the prewriting process, and to debrief them to find out what they do when they move effectively from assignment or idea to completed first draft. Most of all, we need to move from failure-centered research to research which defines what happens when the writing goes well, just what is the process followed by effective student and professional writers. We know far too little about the writing process.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TEACHING WRITING

Our speculations make it clear that there are significant implications for the teaching of writing in a close examination of what happens between receiving an assignment or finding a subject and beginning a completed first draft. We may need, for example, to reconsider our attitude towards those who delay in writing. We may, in fact, need to force many of our glib, hair-trigger student writers to slow down, to daydream, to waste time, but not to avoid a reasonable deadline.

We certainly should allow time within the curriculum for prewriting, and we should work with our students to help them understand the process of rehearsal, to allow them the experience of rehearsing what they will write in their minds, on the paper, and with collaborators.

We should also make our students familiar with the signals they may see during the rehearsal process which will tell them that they are ready to write, that they have a way of dealing with their subject.

The prewriting process is largely invisible; it takes place within the writer’s head or on scraps of paper that are rarely published. But we must understand that such a process takes place, that it is significant, and that it can be made clear to our students. Students who are not writing, or not writing well, may have a second chance if they are able to experience the writers’ counsel to write before writing.

University of New Hampshire

Durham

WHAT DID YOU LEARN?

Directions: Write your answers in pencil or pen on a sheet of paper. Why? It allows you to slow down and think as you compose an answer on paper.

1. What must good writers do?

2. What is the essential stage in the writing process which precedes a completed first draft?

3. Writing is recursive. What does that mean?

4. What is the one principal negative force Murray identifies? Why is it necessary?

5. What do writers do who are engaged in this first force of writing? Be specific.

6. What are the four positive forces that move writers forward towards the first draft?

7. What is rehearsal? What are some of the things writers do in rehearsal?

8. What are the eight signals that tell the writer he/she is ready to write a first draft?

9. Where does the prewriting process take place?

10. If you are not writing well, what is the advice Murray offers you?

THINK ABOUT IT…

11. In a journal entry, reflect upon a pumpkin seed. What is it? What is its purpose? Its potential? What can it become? What are its limitations? What conditions are necessary for it to grow? Thrive? Change? Die? What is its destiny? What journey is it on? What are the hostile forces it faces? What are its odds of success?

12. Take the information you have from 11, and discuss how these same ideas about the seed relate to how ideas become compositions. In other words, explain Murray’s statement that, “There must be time for the seed of the idea to be nurtured in the mind.”

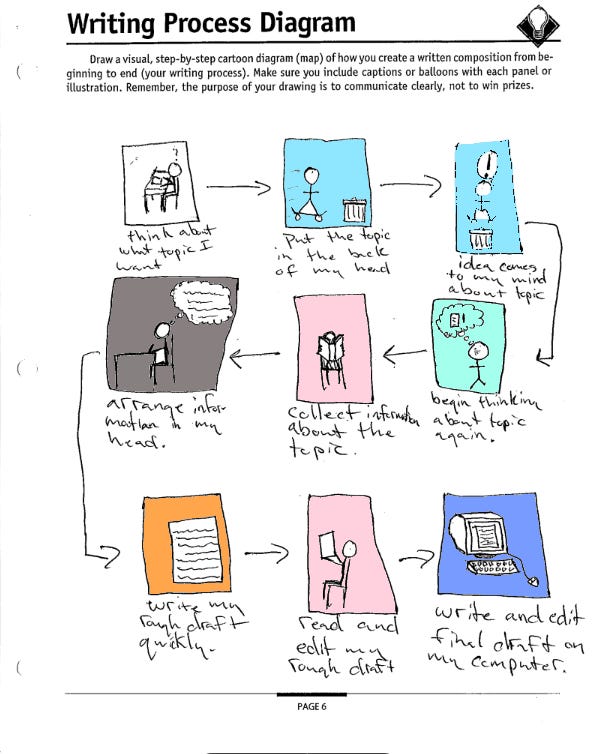

13. Draw a visual, step-by-step map of how you create a written composition from beginning to end. Make sure you include captions or balloons with each panel or illustration. Remember, the purpose of your drawing is to communicate clearly, not to win prizes.

ALL ABOUT YOU…

14. Which signals have you personally experienced? Explain.

15. What do you do when you effectively move from assignment or idea to completed first draft?

16. What are a few things you will try in your next writing assignment based on what Murray tells you about writing well?

17. Consider some of the points Murray raises, then write a reflective essay about how you write. Consider all of the following questions, incorporating your answers into a reflective essay:

a. What pressure you to write?

b. What moves you forward in preparing to write? Why?

c. What keeps you from getting started? Why?

d. In what way does your subconscious work on a writing project?

e. What do you fear about writing?

f. When do you make most of your discoveries when you write?

g. When is the reflective mode of prewriting most useful for you?

h. When is the reactive mode of prewriting most effective for you?

i. Do you see yourself as a writer moving from reactive to reflective over time as you become more experienced? Or are the two modes choices you make as appropriate? Explain.

j. Is one mode more important than the other for certain kinds of writing tasks?

k. What are your signals that you are ready to write?

l. What are the filtering techniques you use as you explore and examine a subject for writing?

This article was an in-class reading assignment students completed at the beginning of the year. All in-class readings were followed by questions I wrote for a close reading of the text, and were reviewed before the end of the first semester portfolio. Students completed a writing portfolio at the end of spring each semester to assess their personal growth as a writer. To determine if the prewriting strategies improved student performance on Oregon’s statewide writing assessment, my master’s thesis study found a strong correlation, at the .001 level of significance, between the number of prewriting strategies a student used and their performance as a writer on the Oregon writing assessment test. You can read the master’s thesis paper here – https://bit.ly/3RX1CdZ

-30-

Dear Rob,

Now I have read it, but it doesn’t describe at all how I write. Okay, maybe the part about carrying an idea around and having little subideas attach themselves like iron filings to a magnet. But my writing isn’t a “process”; it just flows. Especially in poems, it’s as if the Universe is guiding my cursor. I don’t want to overthink writing. I just want to write. Work my way down to that —30— every week.

Do you think your students profited from closely reading Murray and answering your questions? If so, I am content to be an outlier.

I love using-30- too. I found a paper I wrote from 1967 about how I write tonight. The fascination started early — I was 13!

Cheers— Rob